Two Cognitive Cases

This is the first draft of an article I’m developing, I appreciate any commentaries and corrections, which can be sent as reponses.

The study of cognition can be benefited in a number of ways, and people from areas as separate as mechanical engineering, artificial systems and psychology show us that. In fact, from Gödel’s theorem to dynamic systems to molecular genetics, there is some kind of contribution that has been made to the understanding of mind. I want to present two new challengers here, to join the group of things which are useful to understand cognition. In fact to understand in general. They are Recently-Biased Information Selectivity and Happiness.

First I want to talk about selectivity. If one wants to understand more and be able to acomplish more, it is highly likely that he will have to learn (the other option being invent, or discover). We learn more than we invent because it is cheaper, in economic terms. Our cognitive capacity to learn is paralleled in the south asian countries, whose development is funded into copying technologies developed in high-tech countries. Knowledge is not a rival good, that is, the fact that I have it doesn’t imply you can have it too. Knowledge, Newton aside, has nothing to do with apples.

So suppose our objective was to learn the most in the least time, and to be able to produce new knowledge in the least time. There is nothing more cognitive than increasing our descriptive and procedural knowledge in reasonable timing. The first thing one ought to do is to twist the idea of learning upon itself, and start learning about learning. There are many ways to improve learning that can themselves be learned. One can achieve higher efficiency by learning reading techniques. Also she could learn how to use different mental gadgets to learn about the same topic (i.e. Thinking of numbers as sounds, if she usually thinks of them as written, and vice-versa). She also could simply change her material tools, using a laptop instead of writing with pen, writing in a different language to allow for different visual analogies, using her fingers to count. The borders are of course not clear between different cognitive tools. Writing in chinese implies thinking through another grammatical scheme, as well as looking at different symbols, one of this is more mental, the other more material, both provide interesting cognitive connections to other concepts and thus improve thinking and learning. Another blurry technique, without clear frontiers is to use some cognitive enhancer. Coffee, the most widely used one, is a great enhancer. Except that it isn’t. Working as a brain’s false alarm that everything is okaywhn is isn’t, leading to disrythmia, anxiety exaustion etc. Modafinil is much better, healthier, less prone to causing tension. But are these mental or material gadgets? One thing is certain, they are part of the proof that the mind-body dichotomy has no bearing on reality. These are all interesting techniques for better learning, but I suggest they are not as powerful as selectivity.

Recent-Biased Information Selectivity is a pattern towards seeking knowledge, what is informally called an “approach” to knowledge. A Recent-Biased Information Selector is a person who has a pattern of behavior. This pattern is, as the name denunciates, to look for the solution for her problems mostly in the most recent publications she can find. That is, amongst all of her criteria for deciding to read or not to read something, to watch or not to watch a video, to join or not a dance group, being new is very close to the peak. There are many reasons for which this is a powerful technique, given our objectives. The first is the Law of Accelerated Returns, as proposed by Kurzweil(2005). According to it, the development of information technology is speeding up, we have an exponential increase in the amount of knowledge being produced, as well as in the amount of information being processed. This is Moore’s law extended, and it can be extended to all levels of technological improvement, from the invention of the multicellular organism to genomic sequencing, from the invention of a writing system to powerful computing etc… Stephen Hawking (2001) points out that if one wanted to read all that was being published in 2001, he’d have to run 145 kilometers per second, this speed has probably doubled by now (2010). So Information technology in general and Knowledge in particular are increasingly speeding up. That means that if you cut two adjacent periods of equal sizes from now to the past, odds are high there is more than twice the knowledge of the older period in the newer one. If one were to distribute fairly his readings among all there is to be read, he would already be exponentially shifted towards the present. So a fair distribution in order to obtain knowledge is one that decreases exponentially towards the past. Let us say one reads 1000 pages, more or less three books, per month. So if we divide time in 4 equal periods, let’s say, of 20 years, one would have these pages divided according to the following proportions: 1 : 2 : 4 : 8. Now, 1x+2x+4x+8x = 15x = 1000. x=66 We get the distribution of pages:

66 to 1930 – 1950

122 to 1950 – 1970

244 to 1970 – 1990

488 to 1990 – 2010

In general: Let S be the number of subspaces into which one’s division will be made. Let T be the total number of pages to be read. The fair amount of reading to be dedicated to the Nth subspace is given by the formula:

2n-1 · (T / (21+22… 2S-1))

Now, this is not how we usually reason, since our minds are in general linear predictors, we suppose that fairness in terms of learning knowledge would be to read the same amount for equal amounts of time. This is of course a mistake, a cognitive bias, meaning something that is engendered in our way of thinking in such a way that it leads us systematically to mistakes. My first purpose is to make clear that the wisdom in the strategy of dividing cognitive pursuit equally though time is a myth. A first objection to my approach is that it is too abstact, highly mathematical, there are deep assymetries between older stuff and newer stuff that has not been considered, so one should not distribute her reading accordingly. Exactly! Let us examine those asymmetries.

First asymmetry: Information inter-exchange: It is generally taken for granted by most people that the future has no influence on the past, whereas the past has influence on the future. More generally, an event X2 at time T2 will not influence another event X1 at time T1, but might influence X3 at time T3. This of course is false. But we are allowed to make Newtonian approximations when dealing with the scale in which knowledge is represented, that is paper scale, brain scale (Tegmark 2000), sound-wave scale. So it is true for our purposes. From information flow asymmetry it follows that what is contained in older knowledge could have influenced newer knowledge, but not otherwise. This is reason to take the fair distribution, and squeeze it even more towards the present.

Second, asymmetry: Having survived for long enough. This is the main objection I saw against biasing towards the present, it consists of saying that the newest stuff has not passed through the filter of time (this could also be called the “it’s not a classic” asymmetry) and therefore is more likely to be problematic. I have argued elsewhere that truthful memes are more likely to survive (Caleiro Forthcoming) and indeed that is a fair objection to the view I am proposing here. This asymmetry would make us stretch our reading back again. But in fact there is a limit to this filter. One has strong reasons not to read what came just hot out of press (unless there are other factors for it) but few reasons not to read what has been for 2 years in the meme-pool, for instance. The argument is strong, and should be considered.

Third, Conceptual-Scheme Complexity: Recent stuff is embedded in a far more complex world, and in general into a very complex scheme of things, that is, the concepts deployed are part of a complex web, highly sofisticated, deeptly interacting. This web makes the concepts clearer since they are more strongly interwoven with other concepts, theories, experiments etc… The same concept usually will have a much more refined conception today than the one it had two hundred years ago. Take the electron for instance, we have learned enormous amounts about it, the same word means much more today than it did. Even more amazing is the refinement of fuzzy concepts like “mind”, “cognition”, “knowledge”, “necessity”, “a priori” and so on.

Fourth, Levels of Meta-knowledge available: Finally we get to an interesting asymmetry, that is related to how many layers of scrutiny has an area passed through. In the early days we had “2+3·5+(9-3)” kind of maths, then someone notices we’d be well with a meta-symbol for a given unknown number so we had “ X+3 = 2” kind of mathematics…. and someone else eventually figured a symbol could denote a constant, and we had “Ax+By+C = 0” kind of mathematics, there are more layers, but the point is clear. Knowledge2, That is Meta-Knowledge depends on the availability of Knowledge1, same for Meta-meta-knowledge or Knowledge3. In psychology we had first some data regarding a few experiments with rats, then some meta-studies, with many clusters of experiments with rats, then some experiments with humans, then meta-inter-species knowledge that allowed us to compare species, then some theories of how to achieve knowledge in the area, that is epistemology of psychology etc… Now, it is usually impossible to create knowledge about something we have no data about. So there is no meta-knowledge without there being knowledge first. The number of layers is always increasing, for it is always possible to seek patterns in the highest level (though not always to find them!). More publications give us access to more layers of knowledge, and the more layers we have, better is our understanding.

These asymmetries give us the following picture, if we had a fair distribution, we should squeeze it a lot towards the recent past (some 2 years before present) but resist the temptation to go all the way and start reading longterm-useless nonfiltered stuff like newspapers. A simple way to do that is to change the 2 in the general equation for a 3. Some interesting ideas on this topic of selective ignorance deserve mention:

“There are many things of which a wise man might wish to be ignorant.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson

“Learning to ignore things is one of the great paths to inner peace”

Robert J Sawyer – 2000

“What information comsumes is rather obvious: it consumes the attention of its recipients. Hence, a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention and a need to allocate that attention efficiently among the overabundance of information sources that might consume it.”

Herbert Simon, Turin Award winner, Nobel Prize winner

“Just as modern man consumes both too many calories and calories of no nutritional value, information workers eat data both in excess and from the wrong sources”

“If you are reading an article that sucks, put it down and don’t pick it back up. If you go to a movie and it’s worse than The Matrix Revolutions, get the hell out of there before more neurons die. If you’re full after half a plate of ribs, put the damn fork down and don’t order dessert.”

Timothy Ferris – 2007

I’ve shown the names of those I’m quoting, for this gives one tip on exceptions for the no hot-out-of-press rule. That is the argument from authority. The argument from authority is fallacious in its usual form:

Source A says that p.

Source A is authoritative.

Therefore, p is true.

But is reasonable in its bayesian form (“~” is the symbol for “not”) :

Source A says that p. Source B says that ~p.

Source A is authoritative. Source B isn’t.

Therefore, it is rational to consider that p is more likely to be true until further analysis.

The other exception in which we should read what is hot-out-of-press (given our cognitive objective, as always in this article) is when it is related to one’s specific line of work at the moment. Suppose I’m studying Happiness to write a review of current knowledge in the area, this gives me good grounding to read an article published this month, since I must be as up to date as possible to perform my work. Exceptions aside, it is a good strategy to let others filter the ultra-recent information for you and remain in the upper levels of analysis. The same is true of old information, what is relevant is highly likely to have been either preserved, as I mentioned before, or rediscovered, as all the cultural evolutionary convergences show (Diamond 1999,Caleiro Forthcoming ).

First Case Conclusion:

Our natural conception of how to distribute our time in obtaining knowledge is biased in the wrong way, suggesting equal amounts of effort to equal amounts of time. To achieve greater and deeper knowledge, one should distribute her effort with exponentially more reading of more recent periods than older ones. In addition, she should counter this bias with another bias, shifting it even more towards the present but stoping short of it, with an allowance for some basic knowledge filters to operate before choosing what to read. We end up with an exponential looking curve that peaks in the recent past and falls abruptly before reaching the present.

Second case, Happiness

All other things equal, most people would not choose to have every single day of their lifes, from tommorrow onwards, being completely miserable. It is a truism that people do not want to suffer unless it is necessary, and most times not even in that case. Neutrality is good, but not good enough, so, all things equal, it is also true that most people would choose to have countless episodes of deep fulfilling happiness for the rest of their lifes, as oposed to being merely “Not so bad”. Some people have noticed that this is not so unanimous, for instance, Betrand Russell (1930) wrote: “Men who are unhappy, like men who sleep badly, are always proud of the fact.”

I intend to discuss happiness from another perspective, the perspective of cognition. Is happiness good or bad for thinking? Supposing our cognitive objective, as we did before, let us examine happiness. Suppose we don’t care about happiness, we just want to be cognitively good. Contrary to popular legend that thinking equals suffering, and Lennon’s remark that “Ignorance is bliss”, current evidence suggests that happiness is positively correlated with (Gilbert 2007, Lyubuomisrky 2007, Seligman 2002):

Sociability

Energy

Charity

Stronger immune system

Cooperation

Physical health

Earnings

Being Liked

Amount of friends

Social support

Flexibility

Intelligence

Ingenuity in thinking

Productivity in job

Leadership skills

Negotiation skills

Resilience in face of hardship

It is hard not to notice how many characteristics there are on the list, and easy to see how many of them are related to being a better learner, a better teacher, and a better cognitive agent in general. This is true independently of what one studies, if the knowledge is descriptive such as calculus, or procedural such as dancing. There is also the evident fact that depressed people tend to loose productivity dramatically during their bad periods. This gives us good scientific grounding to believe that happiness is important for cognition, to learn better, to achieve more, and to be cognitively more apt in general. So we ought to be happier.

But should we be happier? How much happier? The reason why I started this article is that I was reading in the park, listening to some music, watching people going and coming, families, foreigners, kids etc… It was a beautiful sunny day and I had just exercized, I was reading something interesting and challenging, the music was exciting, I took a look around me and saw the shinning sun reflecting on the trees, a breeze passed amidst the giggle of kids nearby and I thought “This is great!” In fact I thought more than that, I thought “This is great! Still it could be better”. There is some background knowledge needed to qualify the power of this phrase. Once I saw a study that said a joke had been selected among thousands by internet users, therefore it was a scientifically proven funny joke. Now, I’m a happy person. In fact I’m a very happy person. It took me a while to accept that. It is hard to accept that one is the upper third of happiness, because that tells a lot about the human condition, and how happy people are. So I was pondering about this fact that people told me, and that I subjectively felt, and finally science came to my aid. The University of Pennsilvania holds an online-test called authentic happiness invetory. The website has 700,000 members. I did the test twice, with some 14 months in-between. The website provides comparisons among those who took the test, we can take these to be some dozens of thousands of people at least. The first time I did it, it showed “You scored as high or higher than 100% of web users, 100% of your gender, 100% of your age group 100% of your occupational group, 100% of your educational level and 100% of your Zip code”. One year later, the first five bars were still showing 99% and the last one 98%. Thinking I might have been in an exceptionally happy day that time, I took the test again, and to my surprise I was back to 100% in all categories. I knew I am happy, but that was taking the thing to a whole other level. So I was as scientifically comproved to be happy as that joke, I was in the very end of the tail of the curve.

Now think again about that phrase in that scene in the park. “This is great! Still, it could be better.” I was not talking about myself (as I’ve been for one paragraph now) I was talking about Man. If you found yourself in the edge of the curve you’d know what I mean. If this is the best we can do, we are not there yet. I’m not saying that being happy is not great, it is awesome, but it could be much better. I suggest that anyone who had the experience of reading all those “100%” there in the website thought the same, this cannot be the very best, there must be more. This is what brings me to the Humanity+ motto:

Better than well.

The human condition is not happiness-driven. Evolutionarily speaking, we do what we can to have more grandchildren than our neighbors, whereas this includes happines or whether it doesn’t. A mind that was satisficed all the time would not feel tempted to change his condition, so mother nature invented feelings such as anxiety, boredom, tiredness of the same activity, pain etc… Happiness, as designed by evolution, is fleeting, ephemerous (Morris 2004). How could we change that? There are several ways, the most obvious one being chemical intervention. Also technologies of direct stimulation of pleasure centers could be enhanced to accepted levels of safety. Artifacts such as MP3 players also have an effect on happiness since listening to music causes happiness (Lyubomirsky 2007), many artifacts have positive effects on happiness and in the long term may help in improving the human condition. Art, philosophy, spirituality and science have also had long term effects on human happiness. So in order to improve the human condition in the long term, we ought to work in all those bases. This would in turn provide us means to achieve our proposed cognitive goal, through greater cognitively enhancing happiness. Before moving on, I’d like to make an effort of showing a mistake that most people are likely to make, due to some cognitive biases, I’ll first list the biases:

Status quo bias: people tend not to change an established behavior unless the incentive to change is compelling. (Kahneman et al 1991)

Bandwagon effect: the observation that people often do and believe things because many other people do and believe the same things. The effect is often called herd instinct. People tend to follow the crowd without examining the merits of a particular thing. The bandwagon effect is the reason for the bandwagon fallacy’s success.

From Yudkowsky (2009):

Confirmation bias: “In 1960, Peter Wason conducted a now-classic experiment that became known as the ‘2-4-6’ task. (Wason 1960.) Subjects had to discover a rule, known to the experimenter but not to the subject – analogous to scientific research. Subjects wrote three numbers, such as ‘2-4-6′ or ’10-12-14’, on cards, and the experimenter said whether the triplet fit the rule or did not fit the rule. Initially subjects were given the triplet 2-4-6, and told that this triplet fit the rule. Subjects could continue testing triplets until they felt sure they knew the experimenter’s rule, at which point the subject announced the rule.

Although subjects typically expressed high confidence in their guesses, only 21% of Wason’s subjects guessed the experimenter’s rule, and replications of Wason’s experiment usually report success rates of around 20%. Contrary to the advice of Karl Popper, subjects in Wason’s task try to confirm their hypotheses rather than falsifying them. Thus, someone who forms the hypothesis “Numbers increasing by two” will test the triplets 8-10-12 or 20-22-24, hear that they fit, and confidently announce the rule. Someone who forms the hypothesis X-2X-3X will test the triplet 3-6-9, discover that it fits, and then announce that rule. In every case the actual rule is the same: the three numbers must be in ascending order. In some cases subjects devise, “test”, and announce rules far more complicated than the actual answer.” […]

““Hot” refers to cases where the belief is emotionally charged, such as political argument. Unsurprisingly, “hot” confirmation biases are stronger – larger in effect and more resistant to change.”

Let me restate a case of the status quo bias in another form: When people make a decision, they should take only the benefits and costs of what they intend to do, and carefully analyse them. This is fairly obvious. Also, it is complete nonsense. What one ought to do when she is trying to find out about doing or not doing something is to compare that that thing with what she would do in case she didn’t do that thing. Suppose I’m a father who gets his daughter everyday in school. Then some friends invite me to go play cards, I reason the following: “Well, playing cards is better than doing nothing” and I go play cards, leaving my poor child alone in school.

Another important topic is how can someone be happier than he usually is, right now? What is already available? What has been proven to increase satisfaction? The rest of the article is dedicated to this topic. Gilbert (2007) has many interesting words on that, they are worth quoting:

“My friends tell me that I have a tendency to point out problems without offering soutions, but they never tell me what I should do about it.”[…]”… you’ll be heartened to learn that there is a simple method by which anyone can make strikingly accurate predictions about how they will feel in the future. But you may be disheartened to learn that, by and large, no one wants to use it.

Why do we rely on our imaginations in the first place? Imagination is the poor man’s wormhole. We can’t do what we’d really like to do – namely, travel trough time , pay a visit to our future selves, and see how happy those selves are – and so we imagine the future instead of actually going there. But if we cannot travel in the dimension of time, we can travel in the dimensions of space, and the chances are pretty good that somewhere in those other three dimensions there is another human being who is actually experiencing the future event that we are merely thinking about.” […] “it is also true that when people tell us about their current experiences […] , they are providing us with the kind of report about their subjective state that is considered the gold standard of happiness measures. […] one way to make a prediction about our own emotional future is to find someone who is having the experience we are contemplating and ask them how they feel.[…] Perhaps we should give up on rememberin and imagining entirely and use other people as surrogates for our future selves.

This idea sounds all too simple, and I suspect you have an objection to it that goes something like this… “

This fine writer’s message is simple, stop imagining, start asking someone who is there. This is the main advice for those who are willing to predict how happy will they be in the future if they make a particular choice.

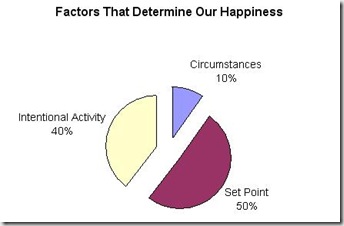

Now, Lyubomirsky offers many other happiness increasing strategies. First, she proposed the 40% solution to happiness. Happiness is determined according to the following graph:

That is, Happiness is 50% genetically determined (that is, if you had to predict Natalie Portman’s happiness, and she had monozygotic twin separated at birth, it would be more useful to know how happy the twin is than to know every single fact you may figure out about Natalie’s way of life, past and present conditions and reactions to life events) , 10% due to life circumstances (This includes wealth, health, beauty, marriage etc…), and 40% due to intentional activities. So, all things considered, if one is willing to become happier right now, the best strategy is to change these last 40%, how can we do it. Here I will list some comproved ways of increasing general subjective happiness. I will not provide a detailed description of the experiments, but those can be found in Lyubomirsky’s book references. My aim here is to give my reader a cognitive tool for increasing her happiness, since I have defended that achieving greater happiness is a good cognitive strategy.

Bostrom, N. 2004 The Future of Human Evolution. Death and Anti-Death: Two Hundred Years After Kant, Fifty Years After Turing, ed. Charles Tandy. Ria University Press. pp. 339-371. Available online: http://www.nickbostrom.com/fut/evolution.html

Diamond, J.1999. Guns Germs and Steel:The Fates of Human Societies. W.W. Norton & Co

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L. & Thaler, R. H. (1991). Anomalies: The Endowment Effect, Loss Aversion, and Status Quo Bias. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5, 1, pp. 193-206

Russell, B. 1930. Conquest of Happiness

Available online: http://russell.cool.ne.jp/beginner/COH-TEXT.HTM

Tegmark, M. 2000. The importance of quantum decoherence in brain processes IN Physics Review E61:4194-4206

Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/9907009

Yudkowsky, E. 2009. Cognitive biases potentially affecting judgment of global risks IN Global Catastrophic Risks, eds. Nick Bostrom and Milan Cirkovic. Oxford

Available online: http://yudkowsky.net/rational/cognitive-biases

2) The human civilization doesn’t look so let’s say… very well organized, it seems like there are important human beings doing stupid things.

2) The human civilization doesn’t look so let’s say… very well organized, it seems like there are important human beings doing stupid things.